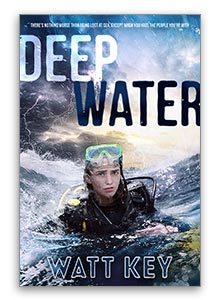

The Inspiration for DEEP WATER

When I was sixteen years old, I was stranded after a scuba dive. Two friends and I had taken a boat out into the Gulf of Mexico. We didn’t have a GPS or any navigational electronics on board. All we had was a compass. We were headed to the site of a sunken ship called the Allen, one of several World War II supply ships sunk in 90 feet of water to create an artificial reef for recreational purposes. Our plan was to find a commercial dive charter already anchored, and once they finished their dives, we’d hurry over and take their place.

My friend Archie and I had been certified divers for a couple of years. Also with us was a boy from Mississippi named Dean, the son of one of my mother’s friends, in town for a visit. He didn’t know much about boats or scuba diving. He just happened to be along for the ride.

That day the Gulf was a calm surface of gentle, heavy swells and the skies were blue. Once we lost sight of land it didn’t take long to locate a charter boat flying the red-and-white dive flag that means they’re anchored with divers in the water. We kept our distance until we saw them preparing to leave. Then we dropped our own anchor just as they were pulling away.

The water was clear enough to see the anchor rope streaming down toward the seafloor, but not so clear that we could see the ship below. It took about thirty seconds for all the rope to spool out. Then Archie put the boat in reverse to make sure the anchor was set and holding. We saw right away that it wasn’t. And just a pull on the rope revealed that it hadn’t even touched bottom. Fortunately the current wasn’t bad, so we had time to lengthen the anchor rope with a ski rope and drop it again before we drifted too far out of position.

Archie and I got into our scuba gear, grabbed our spearguns, and rolled off. We had a great dive; the visibility was good and we speared a stringerful of fish. But when we returned to the anchor to start our ascent, we knew right away that something was wrong. The anchor rope, our lifeline to the surface, was limp. It had either broken or come untied.

We couldn’t afford to analyze what happened. We were running out of air and about to exceed the safe time limit for ninety feet. We had to start a free ascent immediately. Scuba ascents are done slowly so that your body has time to release deadly gases that have built up in your system during the dive. It was going to take us nearly twenty minutes to reach the surface. With free ascents it’s hard to control how fast you rise, and all the while the current is sweeping you away from the dive site. By the time we surfaced we were going to be tired and maybe lost.

When we finally broke into sunlight, there was no one to be seen. The current wasn’t bad, so we doubted that we’d drifted far, but who knew how long it would take Dean to realize something was wrong. And even when he did realize it, he didn’t know how to drive a boat.

The first thing we did was get rid of our fish so that the blood didn’t attract predators. Then I hung my mask at the end of my speargun and began waving it in the air while Archie watched below us for sharks.

After about fifteen minutes, in an unbelievable stroke of luck, a fishing boat happened to pass by and see us. We told the fishermen what happened, and from the higher vantage point of their boat, they were able to see Dean drifting about a quarter-mile away. They got us out of the water and took us to our boat, ending what could have been the start of our own Deep Water adventure. As we suspected, Dean had never even known anything was wrong. After pulling up the ski rope, we saw that it and the anchor rope had come untied.

On that day, preparing myself for a life-threatening situation, I had to draw on skills I’d learned from adults. Then I had to reach beyond that and use my imagination to reason my way around issues I hadn’t been trained for. I’ve often wondered what would have happened that day if the fishing boat hadn’t come along—if we hadn’t been so fortunate. And that’s where the story in my latest novel, Deep Water, came from.

In all of my novels I place my young characters in situations where they initially rely on what they have been taught, but ultimately learn to think for themselves. In Deep Water, a twelve-year-old named Julie, finds herself lost after surfacing from a dive, floating for days, her face exposed to the searing sun. Her dive-instructor father has certainly taught her to wear sunscreen, but now she doesn’t have any. What will she do?

To make matters worse (which is precisely my job as a teller of survival tales), as Julie floats across the Gulf she must deal with a pair of her father’s obnoxious clients, one of whom has severe lung damage from surfacing too fast against her advice and is bleeding from his nose. Julie remembers her father telling her that sharks can smell bloody water from over a mile away. What will she do?

At a time when many kids wall their imaginations in the narrow world of screen-watching and video-gaming, I hope reading my novels help broaden their experiences and break down those walls. I try to put my characters in realistic, life-threatening situations that force them to learn that they can be confident and brave, moral and compassionate, and solve real-world problems. While I have no notion that my novels have ever helped a reader escape a life-threatening situation, I know from thousands of letters and emails received over the years that they have helped many young readers learn to love books and broaden their imaginations in ways that empower them to tackle the outdoors and life itself without fear.