Whenever I tell the story of the time I spent 14 days in the swamp, surviving on only what I could kill with a bow and arrows,  people inevitably ask me why I did it. At first, I thought it was because I was looking for a story. But now, I know better.

people inevitably ask me why I did it. At first, I thought it was because I was looking for a story. But now, I know better.

I left for the swamp as a 19-year-old sophomore at Birmingham-Southern College. But the story starts before that. I was one of twenty-three people in my graduating prep school class. Nine of us were boys and many of us had been together since kindergarten. At a school of that size, it is not hard to be the best at something. Andy was the best soccer player. Scott was the best artist. Archie was the best mathematician. I was the best storyteller and writer.

When I arrived at college, I found myself suddenly immersed in thousands of students. I was no longer the best at anything. I wasn’t even sure that I was average.

While most students seemed to be strolling about the campus, gliding easily in and out of their classes, I was frazzled and confused. I took every spare moment I could find to hide in the library and grip the edges of my school books. I wasn’t as concerned with making great scores as I was with just staying in school. I’d never considered failing, and suddenly it was a looming possibility.

I came out of my first year an unremarkable student, despite feeling like I’d studied twice as hard as most. When I came back to college as a sophomore, I didn’t expect to be an excellent student, but I felt confident that I could get by.

But there was a big part of me that didn’t just want to get by. I wanted to be the best at something again. Hard work and dedication didn’t bother me, I just needed to figure out where my talents were and begin to focus my efforts in the right direction. Although it would take me a while to find this direction, things were about to happen that would get me on my way.

Birmingham-Southern has a one-month-long term in January that they call Interim. Students may select from a list of unusual courses designed to foster creative thinking. If one studies the college handbook carefully, they will also find a clause that allows students to design their own course and have it sponsored by a professor and finally approved by the Interim board. I found this clause my sophomore year and knew immediately what I wanted to place before them.

The initial draft of my proposal was very simple. I wanted to live with two of my friends in the swamps of south Alabama for 14 days with only the following items:

| – Bow and 20 arrows | – Small flashlight | – Iodine tablets |

| – Fletching glue and misc. arrow repair items | – String for fishing & snaring | – Notepad |

| – Sleeping bag | – Axe | – Pencils |

| – Salt | – Shovel | – Camera |

| – Knife | – Fish hooks | – Backpack |

| – Skillet | – One change of clothes | – Candles |

| – 100 Matches | – First aid material | – Toilet paper |

| – Poncho | – Soap |

With our meager list of supplies, we would live off the land, sleep in a shelter we constructed, and eat only what we killed and foraged.

Two faculty members refused to sponsor me before I finally obtained the support of a young psychology professor. She was fascinated with the idea and helped me make the proposal more presentable by adding some required reading. Thoreau’s WALDEN and several books on edible plants and survival skills gave the project a more scholarly edge.

She presented the proposal to the Interim board, and after some initial skepticism, it was accepted. We were shocked. Nothing like it had ever been done at the college.

Word soon spread about campus of our endeavor. It was the conclusion of most that we had tricked the school into letting us spend two weeks at a hunting camp. But I made it clear to my two companions and the rest of the school that I would stick by my self-imposed rules. I was going into the swamp with nothing more than what was on my list and I wasn’t coming out for 14 days.

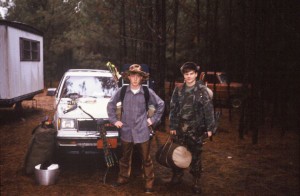

We set out at daybreak on a cold, rainy, January morning. Our destination was a small clearing near a creek that I knew of from past hunting seasons. This was before cell phones, so there would be no contact with others unless we hiked five miles to the closest store.

We set out at daybreak on a cold, rainy, January morning. Our destination was a small clearing near a creek that I knew of from past hunting seasons. This was before cell phones, so there would be no contact with others unless we hiked five miles to the closest store.

The swamp was flooded and we waded through cane thickets and swollen creeks before we finally reached the campsite. Everything we had was soaked through, so we dropped it on the ground and began to trudge about in the rain looking for shelter material.

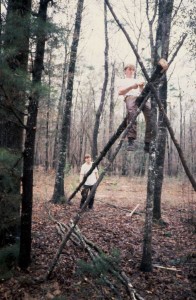

We worked all day constructing a lean-to, sacrificing our ponchos for the underside of the roof. It was miserable work, standing in the downpour like cows in a field with nowhere to go. Rain dripped from our bangs and off our noses. Our clothes clung to us like pastry dough. None of us said much as we created our walls with palmetto fronds and pine boughs.

We worked all day constructing a lean-to, sacrificing our ponchos for the underside of the roof. It was miserable work, standing in the downpour like cows in a field with nowhere to go. Rain dripped from our bangs and off our noses. Our clothes clung to us like pastry dough. None of us said much as we created our walls with palmetto fronds and pine boughs.

That evening the rain moved out and we faced our creation under a gray, dripping sky. If the rain came again the shelter would not keep us totally dry, but would have to do for the first night.

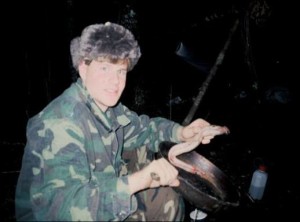

We had not eaten all day and our stomachs were nauseous with hunger. Fortunately, a cottonmouth snake, flooded from its den, was seen moving sluggishly in the leaves. I shot it from about 10 feet away with my bow and amazed myself by hitting it. None of us were experienced bow hunters and that had been a concern.

I tied a string around the snake’s neck and hung it from a tree. After peeling the skin off like a sock, I slit the belly and removed the intestine. Finally, I cut the head off just under the string and placed the white meat into the skillet with some rainwater where it continued to squirm like it was whole.

It took some searching to locate wood dry enough to get a fire going, but we were soon watching the snake boil. It continued to squirm in the skillet even as the meat turned flaky and white. After about 10 minutes, I pulled it out and cut it into sausage-length pieces on a log. As we lifted the pieces to our mouths, we could still feel the meat pulsing between our fingers.

It took some searching to locate wood dry enough to get a fire going, but we were soon watching the snake boil. It continued to squirm in the skillet even as the meat turned flaky and white. After about 10 minutes, I pulled it out and cut it into sausage-length pieces on a log. As we lifted the pieces to our mouths, we could still feel the meat pulsing between our fingers.

We went to bed not long after dark. With no light except for our meager candles, there wasn’t much else to do. The swamp sounds closed around us and small creatures rustled in the leaves near our faces. It wasn’t long before the rain started coming down again. We buried ourselves fully clothed into the wet sleeping bags and lay pressed between the walls of the lean-to. It was a long night of silence and dripping water and waiting for dawn.

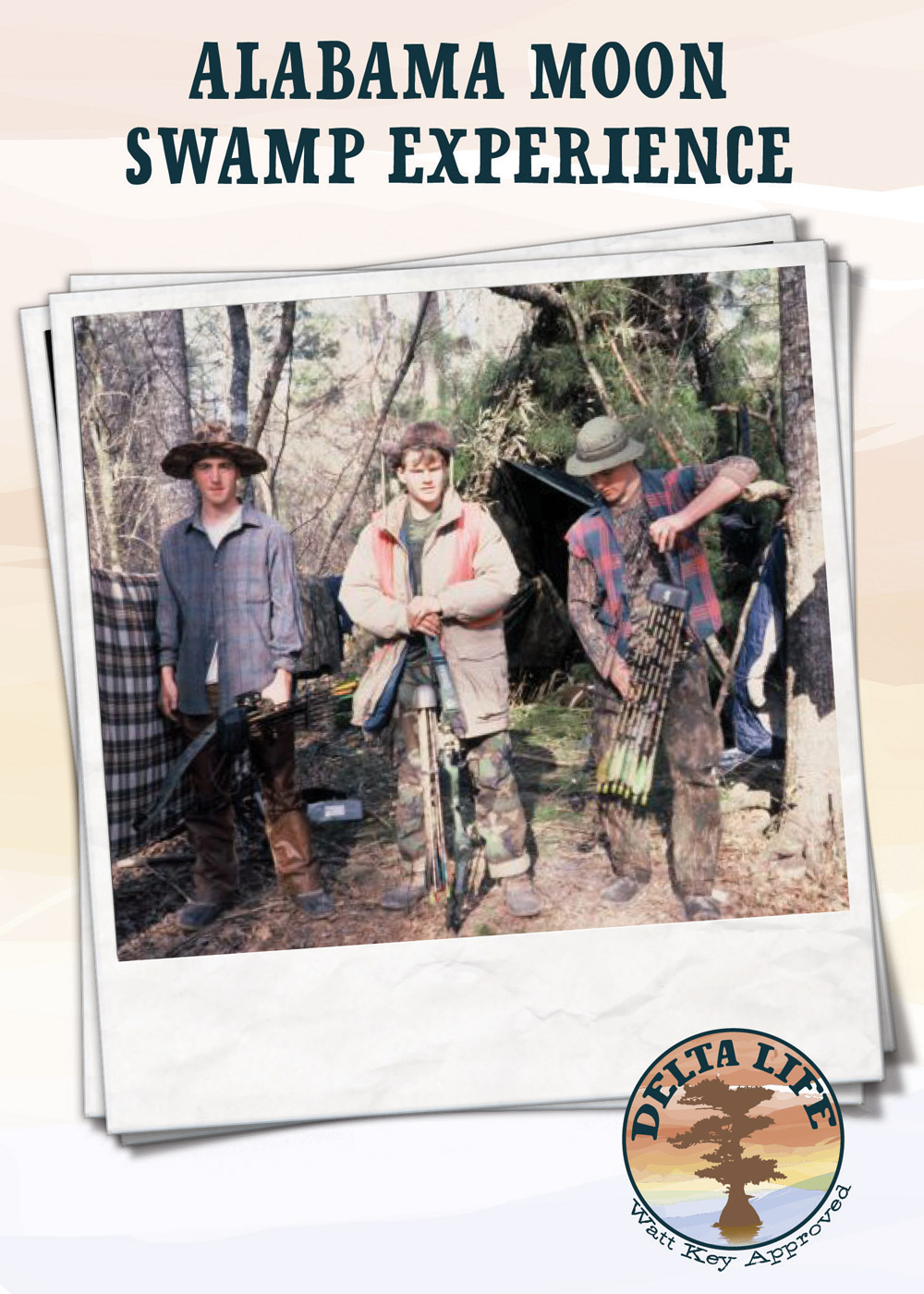

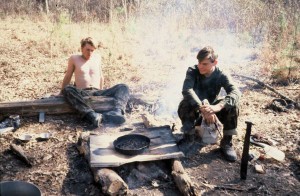

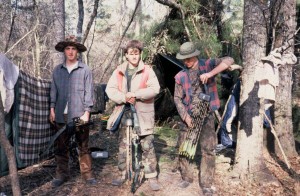

The next morning we set out in different directions to hunt the river bottom. It wasn’t long before I came across a group of six wild piglets, no bigger than dachshunds. They didn’t know what to make of me and it was easy to shoot two of them at close range. In the picture that’s us (I am on the far left), ready to hunt our first morning. The sun is back out and our spirits are high.

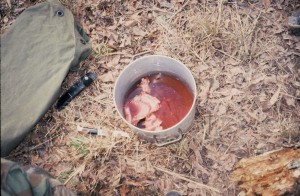

When I got back to camp, my friends had not killed anything and I was thankful for the little meat that I carried. We skinned and  quartered the piglets and set the meat to boil in the cooking pot. Meanwhile, I took their livers from the pile of intestine and set the rest aside for snare bait. I browned the livers in the skillet and ate them while my friends watched. They refused their portions, concerned about trichinella worms commonly found in pork liver.

quartered the piglets and set the meat to boil in the cooking pot. Meanwhile, I took their livers from the pile of intestine and set the rest aside for snare bait. I browned the livers in the skillet and ate them while my friends watched. They refused their portions, concerned about trichinella worms commonly found in pork liver.

We didn’t have ample water to rinse our piglets. When the meat had boiled about 15 minutes, we let it cool and then ate it from the bloody water. Finally, we singed the hair off the skins in the fire, and made pork cracklin’. Nothing but the head and feet went to waste.

I found the piglets again the third day and killed two more. Once again, the meat turned out to be all that we would have. Beside the fact that we didn’t have enough, the young pork was completely lean and we began to crave fat. The thin pork cracklin’ was as much as we could get and we licked our fingers of every bit of grease we could wipe from the skins.

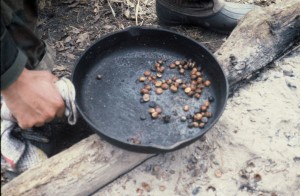

On day four we ate leftover piglet for breakfast. We were unsuccessful on our morning hunt and decided to start shelling and toasting acorns. They have a bitter taste resulting from the tannic acid they contain. We boiled them and  strained them through a sock seven or eight times before toasting them in the skillet. The result was much the same as a very bitter peanut and did little to satisfy our stomachs. You can taste them in your burps for days. We got very tired of eating them.

strained them through a sock seven or eight times before toasting them in the skillet. The result was much the same as a very bitter peanut and did little to satisfy our stomachs. You can taste them in your burps for days. We got very tired of eating them.

We also made tea that day by pulling green needles from the branches of a loblolly pine, breaking them apart like spaghetti, and boiling them in the  cooking pot. The tea was excellent. From that day on, we all looked forward to sitting about the fire and drinking the warm, weak brew.

cooking pot. The tea was excellent. From that day on, we all looked forward to sitting about the fire and drinking the warm, weak brew.

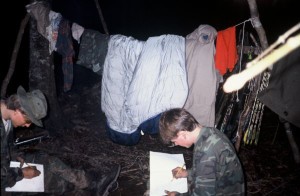

As night fell over us, we wrote in our journals by candlelight. Then we crawled into the shelter one by one, none of us speaking. I lay in the darkness craving the lemon pie that my mother made. Later, I would learn

into the shelter one by one, none of us speaking. I lay in the darkness craving the lemon pie that my mother made. Later, I would learn  that one of my friends was thinking of fried chicken and the other of roast beef and provolone sandwiches.

that one of my friends was thinking of fried chicken and the other of roast beef and provolone sandwiches.

The hard rains we’d experienced the first few days had moved on. The skies were clear and the weather cold. Some mornings the ground was frozen and  crunched under our boots. Occasionally we had to break ice to get to water. The cold temperatures were tolerable. What we dreaded was rain.

crunched under our boots. Occasionally we had to break ice to get to water. The cold temperatures were tolerable. What we dreaded was rain.

On the evening of day five, one of my friends killed a rabbit. Although just as lean as the pork, it was the best tasting meal we were to have. It was becoming clear that killing large game was not going to be as easy as we’d imagined. The deer and wild hogs, plentiful in the area, seemed to know we were about. They smelled us and heard us. Our bows and arrows were useless against the fleeing animals. Even when we sat in wait for them on game trails,we were so malnourished that our bows were hard to pull back and our hands trembled and sent the arrows wild.

On the evening of day five, one of my friends killed a rabbit. Although just as lean as the pork, it was the best tasting meal we were to have. It was becoming clear that killing large game was not going to be as easy as we’d imagined. The deer and wild hogs, plentiful in the area, seemed to know we were about. They smelled us and heard us. Our bows and arrows were useless against the fleeing animals. Even when we sat in wait for them on game trails,we were so malnourished that our bows were hard to pull back and our hands trembled and sent the arrows wild.

We learned what it felt like to starve. The hunger pains and irritability we associated with a late lunch were nothing like the real thing. It was not painful at all, but a slow loss of energy. And trudging through the bottomland searching for game only made us weaker. We wanted to lie in the leaves and stare at the treetops.

The next day I shot an armadillo that was digging in the leaves close to the camp. An armadillo’s senses are so dull that it is not hard to walk up to one and nudge it with your foot. Perhaps the fact that they usually have their head buried in the dirt looking for sustenance has something to do with this. They eat root and grubs and carrion. They are dirt buzzards.

The next day I shot an armadillo that was digging in the leaves close to the camp. An armadillo’s senses are so dull that it is not hard to walk up to one and nudge it with your foot. Perhaps the fact that they usually have their head buried in the dirt looking for sustenance has something to do with this. They eat root and grubs and carrion. They are dirt buzzards.

I cut him out of his shell and sliced the oily beet-red meat from his back. After browning the cubed meat in the skillet, I stabbed a piece with my knife and ate it. It was theworst-tasting meat I had ever consumed. We ate it all. Then I licked at the white jelly fat that we scraped from the underside of its shell. The fat oil coated our hands and mouth with an intolerable stench that would be with us for days.

As horrid as it was, the armadillo meat gave our bodies a tiny bit of fuel. Enough so that I could rise and hunt again the next morning. My spirits were high, despite our obvious failures. But the forest began to reveal itself to me as something cruel. It wasn’t the expanse of mystery and adventure that had remained in my memories since childhood.

Over the next few days, we drank from the swamp like dogs from puddles. We ate nothing. The acorns gave so little sustenance that we gave up on them. The last of the piglet group had disappeared. Pine needle tea in front of the fire was all we had to write about in our journals. We studied our edible plant books and searched desperately for something we had overlooked. I read one article about pine bark being edible and rushed off to chew on a pine tree. It tasted exactly as I’d imaged. Like gargling turpentine. I spit it out and returned to the book. Then I found another article about the suitability of palmetto roots. We had palmettos all through the river bottom not far from us. I rallied my companions and we set out in search of them.

Over the next few days, we drank from the swamp like dogs from puddles. We ate nothing. The acorns gave so little sustenance that we gave up on them. The last of the piglet group had disappeared. Pine needle tea in front of the fire was all we had to write about in our journals. We studied our edible plant books and searched desperately for something we had overlooked. I read one article about pine bark being edible and rushed off to chew on a pine tree. It tasted exactly as I’d imaged. Like gargling turpentine. I spit it out and returned to the book. Then I found another article about the suitability of palmetto roots. We had palmettos all through the river bottom not far from us. I rallied my companions and we set out in search of them.

We spent most of an afternoon digging. It took almost 20 minutes to get each plant out of the ground. Then it took another 20 minutes to get at the edible heart of the root which was about the size of half an asparagus. It tasted much the same as heart of palm, but like the acorns, we soon decided our efforts would be better spent on hunting.

The swamp had been flooded since our arrival, and there was no place of confined water to try for fish. We decided to spend the morning of day 10 making the journey to a pond about a mile away in the piney woods.

We were weak. The struggle though a flooded cane thicket between the shelter and the pond left us exhausted. Finally, we reached our destination and began hunting for bait. One of us found a cache of dirt dobber larvae beneath a rotten log and we put these on our homemade fishing poles and began to catch fish immediately. The fish were smallbream about the size of sardines. We built a fire on the spot and roasted them on sticks. With only four of these little fish apiece, they did little to ease our hunger, but the act of eating again was encouraging.

We were weak. The struggle though a flooded cane thicket between the shelter and the pond left us exhausted. Finally, we reached our destination and began hunting for bait. One of us found a cache of dirt dobber larvae beneath a rotten log and we put these on our homemade fishing poles and began to catch fish immediately. The fish were smallbream about the size of sardines. We built a fire on the spot and roasted them on sticks. With only four of these little fish apiece, they did little to ease our hunger, but the act of eating again was encouraging.

That night, clouds moved in and we were fearful of rain. We drank our pine needle tea and at some point one of my companions wandered off to try and defecate. None of us had used any of the toilet paper since we’d arrived. Our bodies used anything we put in them for energy.

No rain fell that night, but the forest was dark and depressing the following morning. Only two of us got up to hunt. The other was discouraged and had made up his mind that he was going to wait out the 14 days on his back. Perhaps his method was wise. We didn’t eat again the rest of our stay.

We walked out of the forest one minute after midnight on the 14th day. The rain was starting to patter the leaves as if to warn us of a final death blow should we not leave that place. I’d lost 15 pounds and couldn’t sit without feeling pain in my tailbone. My hands and face were covered in soot and grease and pine sap. My teeth felt like they were coated with pond scum. Small cuts all over my fingers were red and puffy with infection. None of us had used toilet paper in 14 days.

Our first stop was the closest grocery store about 40 miles away. We walked through the sliding doors at one o’clock that morning, side by side like starving gunfighters. None of us said a word as we split off in separate directions, honing in on the foods we craved.

We met again in the parking lot, sitting in the truck and eating in silence. Once we set out again, we had only gone a few miles before we had to stop and puke on the roadside.

It would be several days before my friends’ stomachs returned to normal size and they could keep food down. For me, it would be much longer. After two weeks, when I was still not able to retain solids, my companions diagnosed me with trichinosis. They claimed this was a result of the hog livers I’d eaten. As the rumor of my situation with worms began to spread, I decided it best to get a doctor’s opinion immediately. I did. He said that I was worm-free and that my stomach would return to normal in time.

After a couple of weeks, I was eating without problems and slowly gaining back the weight I’d lost. We gave a presentation of our slides to the college and those who thought we’d spent two weeks sluffing off at a hunting lodge were convinced otherwise. Our self-designed course did not receive a letter grade, but was approved with either a pass or a fail. It was somewhat ridiculous when the college announced that we’d passed.

With the distance of 15 years I can see more clearly how those two weeks fit into my life. I wanted to be a writer. My instincts told me that to be a successful writer I would have to be original. And I would have to be confident.

With the distance of 15 years I can see more clearly how those two weeks fit into my life. I wanted to be a writer. My instincts told me that to be a successful writer I would have to be original. And I would have to be confident.

Sometimes the story is not the story.